| Boyle Farm - Mr Uppercrust |

There is little doubt that St. Leonards felt his exalted position very keenly. He was proud and haughty. An ostentatious man, who meant his presence to be felt. Even one of his own cabinet colleagues pronounced him: "waspish, overbearing, and impatient of cricitism" (263).

From the lower orders of society he expected to be treated with awe and respect. An obligation they were not always inclined to bestow upon him. At least out of earshot. Behind his back he was usually referred to by the villagers as "Mr. Uppercrust". Even the youngsters knew him as "Lord Teddy" (264).

He was at his most magisterial when it came to his estate. It was his own little kingdom, and he was its ruler. Woebetide to anyone who thought otherwise. Although some people were not always to be awed - as we shall see.

The first occasion which comes to notice happened around 1852. A local poulterer named Wyatt kept ducks, which would occasionally fly to the river and settle on the eyots and riverside lawns. Much to the annoyance of the lord of Boyle Farm. Who thought he would soon put a stop to that little game. He detailed his gardener to capture and imprison any fowls which encroached upon his lands. Which he did. But, probably realising the somewhat dubious legality of this exercise, sent their value round to the owner in payment, and the birds presumably ended up as roast duckling on the family table.

This, of course, did not stop further birds from the same performance. Each time they did so the offending fowl was seized. However, St. Leonards soon got fed up with continually paying for them. Instead he informed Mr. Wyatt that he had them and that they would be returned to him on payment of two shillings and six pence in restitution for the damage they had caused, plus nine pence for their keep. This the poulterer resolutely declined to do. So they stayed at the mansion, eating to their heart's content, and soon becoming an acute embarrassment to the peer. So much so that eventually to get rid of them he told Mr. Wyatt he could have them all back for the paltry sum of one shilling. But still he was adamant. He was not going to kowtow to "Mr. Uppercrust".

Instead he sued the noble lord for the return of five ducks and one gosling which had been seized plus ten shillings damages. His computation of the value of the eggs and little ducklings which the birds had produced during the time of their enforced incarceration, now extending to nearly two years. All of which had been lost to him.

The case was brought before a judge and jury at Kingston County Court, who found for the plaintiff and against the great lawyer. His damages were assessed at thirty shillings. The jury decreeing that there was no evidence to prove just how many eggs the birds may have laid during the time of their retention, or what had become of them (265).

The case did prove, however, that even a humble poultry-keeper can sue and even defeat a high and mighty legal grandee.

Still it was not long before somebody else's fowls were invading his lordship's preserves and arousing his wrath. In 1864 he yet again impounded some birds, and sued a Mr. Derbishire for five shillings damages, due to the trespass of his ducks on the lawns of Boyle Farm. Again the case was brought before the county court. A man-servant attended on behalf of St. Leonards, who admitted that the only damage that the birds caused was by them running across the lawns and leaving their feathers around. The judge, Mr. J.F. Fraser, who seems to have been well biased in favour of the peer, said that no doubt this was a discomfort, and gave judgment for two shillings damages. The defendant, not wishing to allow "Mr. Uppercrust" the satisfaction of a moral victory, said he would much rather put ten shillings in the poor box; to which the judge replied, "I can't do that for you. You are bound to keep your ducks on your own ground". Defendant: "I am sorry I can't catch them" (Great laughter). The judge: "Then St. Leonards will catch you" (More laughter) (266).

The great baron's next foray against those whom he thought were invading the sanctity of his little principality, involved the anglers on the Thames.

He was, as we have seen, the owner of the two islands in the river. In July 1862 a Mr. Grissell of Hampton Wick complained to the Thames Conservancy that Lord St. Leonards had interfered; with him whilst he was fishing between the bank and the islands. The Conservancy, therefore, wrote to his lordship informing him that the river was not his property, the public had a right to its legitamate use, over which he had no power to interfere (267).

This missive, however, seems to have failed in its purpose. For exactly three years later we find his lordship involved with yet another angler. Again the fisherman was not daunted by the great peer, or frightened off from what he considered his lawful right.

His name was Thomas Powell, and lived at Long Ditton. He wrote to the local newspaper: "In the interest of myself and brother anglers about Thames Ditton, I write to know whether Lord St. Leonards has a right to order off and prevent anglers fishing the Thames opposite his lordship's lawn. I was fishing about 40 yards, as far as I can guess, from the lawn shore, when his lordship sent a servant and demanded my name and address, adding that his lordship does not allow anyone to fish that spot. Being under the impression that the Thames was free to anglers, I confess I was much astonished. I had not, nor have, the remotest idea of annoying Lord St. Leonards, but I cannot understand what right he has to thus interfere" (268).

One wonders how many anglers, perhaps more timorous than these, were intimidated by "Mr. Uppercrust" into giving up their right to fish how, when. and where, they might.

|

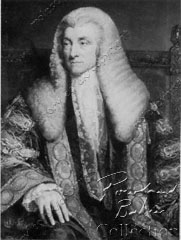

Lord St. Leonards in his robes as lord-chancellor |

In some two years between 1868 and 1870 Lord St. Leonards was the victim of a succession of very elaborate pettifogging practical jokes, but jokes of a particularly biting and malicious kind.

One such occurred in February 1869 at the time of his eighty-eighth birthday. A number of tradespeople and professional men, both local and from town, each received orders instructing them to deliver various goods and services to Boyle Farm. The High Street was the scene of utter bedlam as they all arrived - dozens of them - at the same time. Even a doctor had been summoned to treat some supposed malady (269).

These fallacious instructions continued to be sent on and off for several months, usually to well-known and highly-respected shop keepers in London, directing certain items to be sent to Boyle Farm.

In desperation the peer sent a letter to The Times setting out the details, in the hope that businessmen would check to ascertain whether any orders they received purporting to come from him were genuine or not (270).

This arose chiefly out of one particular duplicity, which was sent to Messrs Emanuel, the jewellers, instructing them to manufacture seven expensive lockets, one to be presented to each of his daughters. The details of the construction of which were specifically laid out - they were to be round and to have his initials and coronet displayed in diamonds. The cost of each was not to exceed £30. What made this attempt more exasperating than the others was the fact that for the first time the hoaxer had actually forged his lordship's signature.

Another trick which caused the family inconvenience, involved one of his daughters who was on a visit to Torquay. Just as she was preparing for dinner one evening a telegram arrived, purporting to come from the butler at Boyle Farm, informing her that Lord St. Leonards was seriously ill. She immediately cancelled her plans, and travelling all night, arrived at Thames Ditton at half past seven in the morning, expecting to find her father on his death bed, but only to discover him as fit and well as an eighty-nine year old could be (271).

However, the deception which caused the most distress and annoyance, occurred when an order was sent to a monumental mason instructing alterations to be made to Lady St. Leonards tomb in St. Nicholas' churchyard, with an entirely fictitious inscription to be made to it (272).

Because of St. Leonards' rather pompous and despotic temperament he undoubtedly had made many enemies during his lifetime who would probably have liked to get back at him. But who would go to these lengths? In spite of the employment of the best detective brains from Scotland Yard no perpetrator of the deceptions was ever discovered, and they ceased as abruptly as they had started. They were obviously committed in order to present the utmost indignation and discomfort to the recipient as possible. The fact that the author had access to the peer's signature and could copy it infers that it was somebody at least well-known to him.

An article in one newspaper professes to have traced the perpetrator of the jokes to some disgruntled men-servants of the peer's, including his long-serving butler. But Lord St. Leonards was prompt to refute this (273).

Although no proof was ever found, and doubtless at this stage never will be found, suspicion is implied that Lord St. Leonards' own grandson and his heir may have been involved.

The baron's eldest son, Frederick, died unmarried in 1844; and his second son, Henry, in 1866, leaving four children, the eldest son of whom, named Edward Burtenshaw Sugden after his grandfather, became heir to the peerage (274).

St. Leonards was just as domineering to his family as to anyone else. The archtypal pater familias of Victorian England, whose word was law and must be obeyed.

The grandson, whilst on holiday in Italy, made the acquaintance of a young lady to whom shortly afterwards he became matrimonially engaged. The baron was livid to think that his heir had contracted this betrothal without so much as seeking his views and approbation. He immediately drafted a codicil to his will, cutting the lad's inheritance down to just £800 a year if he went ahead and married the girl in question. When the fair lady became aware of this prescription she at once broke off the engagement(275).

For a short time grandfather and grandson became reconciled, but before long the reckless youth threw it all away by becoming affianced to yet another lady. Again without grandparental knowledge or sanction. Which caused the peer even greater anguish, and forthwith to change his will once more. Virtually cutting his grandson off entirely. (276).

In fact, this will was to create a sensation after the baron's death. A cause celebre which for the first time established the right of the admissibility of secondary evidence in proving the contents of a will.

Lord St. Leonards died at Boyle Farm on 29 January 1875, a few weeks before his ninety-fifth birthday, and was buried by the side of his lady in St. Nicholas' churchyard (277).

He was undoubtedly the most outstanding personality ever to have lived in Boyle Farm. In spite of his waspishness, he had a kindly nature. Even after Lady Haddington's aloofness caused his abrupt departure from Ireland in 1835, he sent a letter to her husband expressing the sentiment: "I cannot leave without apprising you that I blame no one in the matter and never shall"

(278).

Of his exhaustive knowledge of the English legal system there is absolutely no doubt. He was unrivalled in his time in the branches dealing with conveyancing and trusts. He wrote many authoritative works on the law, especially dealing with these subjects (279). On the chancery bench he was recognized for the fairness of his verdicts. "He nearly as possible realised the ideal of an infallible oracle of law. His judgements always delivered with remarkable readiness, were very rarely reversed, and the opinions expressed in his textbooks were hardly less authorative. As a law reformer he did excellent work in the cautious and tentative spirit dictated by his nature and training" (280).

Even his political opponents acknowledged his impartiality. The Radical Party newspaper - The Freeman's Journal - said on his retirement as lord chancellor of Ireland: "A better Chief Judge in Equity never presided in the Court of Chancery, and never will sit there, nor one who gave such unmixed satisfaction to the bar, the solicitors, and the public; and we have not been able to trace an instance in which he allowed his political opinions or his party view to interfere with the due administration of the law" (281)

When it is considered that this was all achieved with practically no formal schooling, the results are all the more remarkable.

As has already been said his lordship's passing brought about a legal precedent. When the time came for the reading of his will, no will could be found. It was common knowledge that he had executed not only a will but several codicils as well. However, none was in the deed box where they usually were, nor indeed anywhere else either. In spite of a reward of £5,000 which was offered for information leading to their return (282), the elusive documents were never discovered.

In the absence of proper papers his hated grandson, by now the new Lord St. Leonards, claimed the whole estate as intestate heir at law.

However, Miss Charlotte Sugden, the chancellor's unmarried daughter, who lived with him and acted as his unpaid secretary and amanuensis, had been present when the testament and codicils had been drawn up, had read them through thoroughly several times, and understood their contents by heart, knew that this was not her father's wish.

In fact, it seems that the family was fully convinced that it was the new peer himself who was responsible for abstracting the will from its receptacle and for its destruction. They took their case to the probate court. Charlotte and others, the witnesses to the documents, gave evidence as to their existence, the dates on which they were drawn up, and their exact contents. This testimony was accepted by the court, the judge pronouncing: "I can find as a fact that the will of 1870 was duly executed and attested; that the will was not revoked by the testator; and further I find that the contents were as set out in the declaration" (283).

Boyle Farm, its contents, and most of the peer's other property, passed to his second son, the Rev. Frank Sugden, vicar of Hale Magna in Lincolnshire, who resigned his living and came to live at Thames Ditton.

Before Lord St. Leonards had died he made a present to his daughter, Charlotte, of a number of meadows lying between Summer Road and the Thames, on which to build a home for herself after his death. This was done, and in the house, which was called "Riversdale", she retired until her own death on Sunday 7 July 1895, after a long illness. She was buried in the same vault as her parents (284). "Riversdale", later renamed "The Lawn", was demolished about 1925. Its site is now occupied by Riversdale Road.

The Rev. Frank Sugden died in 1886 (285). He had not occupied Boyle Farm for several years. In 1884 it was leased to a Mr. J.M. Livesey (286). The estate now devolved on the second Lord St. Leonards, the grandson disowned by the first lord. Who had meanwhile continued in the news. A few years after their marriage his wife had left him, taking their daughter and sole offspring with her. He sought from the court a decree of restitution on conjurgal rights, which his lady contested, charging her husband instead with adultery. The peer denied this, but judgement was granted in her favour, with a judicial separation and custody of the child (287). A few months later his lordship was declared bankrupt (288).

On 15 July 1886 a judge of the High Court decreed that the whole property - house, contents, and land - must be sold in order to settle the estate (289).

A few months later a start was made on disposing of the valuable assests inside the house-paintings, furniture, china, plate, and books. Most of which had been collected by lord-chancellor St . Leonards, but some had graced the rooms since the time of the Boyles and Fitzgeralds. Still they all had to go. So great was the accumulation of artistic treasures that it took seven days to pass all of the lots under the hammer. The catalogue of items in the collection shows just how rare it was, comprising:

"old French, English and other furniture, including Reisner, Buhl, Chippendale, Sheraton, Adam, marquetrie, etc. Rare specimens of Sevres, Chelsea, Dresden, Oriental, and other china. The valuable oil paintings includes examples by:- Kneller, Rubens, Turner, Zucchero, Rembrandt, Ruysdel, Romney, Vandyck, Breughel, Cuyp, Lely, Possin, Reynolds, Velasquaz, Watteau, Caneletti, Tintoretto, and Vandermeer. Water-colours by:- Copley, Fielding, Turner, Proust, Rowlandson, and others. The library of about 7,000 volumes includes some scarce works, and the valuable law library; and about 5,000 oz. of silver plate" (290).

The house with its immediate surrounding lands, amounting in all to almost twenty-two acres, was next offered for sale. It was auctioned at The Mart in London on 15 July 1890 (291).

In the particulars of sale it was described as: "An old-fashioned mansion house, charmingly situate on the banks of the river Thames at Thames Ditton, in the County of Surrey, facing the grounds of Hampton Court Palace, surrounded by beautifully timbered and totally secluded grounds, which have an uninterrupted frontage of 700 ft. to the river Thames. There are also two eyots in the Thames, and the house contains on the ground floor, noble entrance-hall and a suite of rooms communicating and commanding views of the river, library, &c.; adjoining the entrance-hall is the staircase hall, with a flight of stone stairs leading to the first floor, on which is a gallery around the entrance-hall, large library with a bow window overlookin the river and Hampton Court Park, and six bedrooms, three dressing rooms, and other rooms; on the second and third floors are bed and dressing rooms and servants bedrooms. The servant's offices comprise - on the ground floor, servant's hall, housekeeper's room, linen room, butler's pantry, kitchen, scullery, two larders, dairy, two wine cellars, &c. In the grounds near the entrance gate is a four roomed lodge" (291).

The purchaser was a Mr. Herbert Manwaring Robertson, of High Elms, The Green, Hampton Court, and by an indenture dated 1 December 1890, the property was formally conveyed to him from Lord St. Leonards (292).

The concluding part of the estate - that land lying between the St. Leonards and Portsmouth Roads, containing somewhat over seventeen acres - was auctioned on 23 June 1891, and bought for building purposes (293). Soon afterwards the Portsmouth and River Avenues were laid across it.

These sales did not conclude the new Lord financial troubles. He moved to Ireland, where he died in March 1908 (294). He left just £4,816 18s. 5d., with net personality nil (295).

As has been said, the sale particulars described the building as "an old-fashioned mansion house", and old-fashioned it was then indeed. Mr. Robertson's first object, once he had taken possession, was to attempt to bring it more into keeping with contemporary taste. Luckily his efforts were concentrated mainly on the external appearance. Leaving the interior, especially the decorations effected by Miss Boyle in the eighteenth century, very much as it was.

However, the face-lift on the outside was comprehensive indeed. Firstly all the gables, garrets, and pinnacles, conceived in the alterations of the 1820s, were swept away, and replaced with a pitched slated roof, hipped at either end, which spread over the entire main body of the house, with smaller matching roofs over the side wings. The slightly protruding three-bay section on the entrance front was ennobled with a triangular corniced pediment. The walls were then entirely encased with deep red facing bricks, of very good quality, and extremely well and expertly fitted onto the existing walls. Finally the eaves throughout were supported by a classical dentilated cornice, with a matching string course across the semicircular bay on the river front. This brought the house to the state we see today. A much more charming affair than it was before. (See illustrations).

|

Boyle Farm after modifications of 1892 The river front |

|

The entrance front |

The works were completed by the winter of 1892/3, and Mr. Robertson celebrated by throwing a grand ball to introduce his friends to the newly renovated and enriched mansion (296).

In Mr. Robertson, it seems, we had a man of a temperament very akin to that of Lord St. Leonards before him, when it came to the sanctity of the little kingdom of Boyle Farm. He, too, was soon imbroiled in litigation.

One fine summer' s day in July 1900, a gentleman named Samuell invited his friend Mr. Grundtvig, his wife, and two transatlantic female cousins, to accompany him for a trip up river in his private launch. They left Richmond in the morning, taking with them a luncheon basket, hoping to find a restful place whereon to enjoy an alfresco meal. What they found turned out to be far from restful, and far from enjoyable. Something which marred their memory of the excursion for many days to come.

By lunchtime the party had arrived at Thames Ditton, and espied Boyle Farm Island. What more pleasant and delightful spot could be imagined on which to partake of a quiet picnic than this little uninhabited island?

Completely missing (or deliberately ignoring) the notices dotted around the shore warning that it was a private estate, they landed. Out came the picnic basket, and they started to tuck into their luncheon. But not for long! Trouble soon arose on the horizon in the shape of an irate Mr. Robertson, who had spotted intruders on his territory, and had rowed across accompanied by his son and a big dog. In a somewhat bellicose fashion he informed them that they were trespassing, pointed out the notices, and demanded that they vacate the island forthwith.

Had Mr. Robertson approached the party in a less aggresive mood they probably would have left without trouble. As it was in Mr. Grundtvig he found a rather kindred soul. A man who hated being shouted at. And he declined to be rushed into leaving. The two became very agitated, and a war of words ensued between them. At one stage Mr. Robertson threatened to throw the picnic basket into the river if they did not move it, and made as if to do so. Mr. Grundtvig made a grab for it, and in the ensuing melee it was not the basket which was cast into the water - it was Mr. G.

Mr. Samuell aided his friend from the river and back on to dry land. Whereupon the owner called to his son to bring the dog over, and urged it to attack the intruder. Which it did. Grabbing him by the seat of his trousers and biting a piece right out of the cloth. The party eventually boarded the launch again, and proceeded to Hampton Court, where they procured a new suit of clothes for the wet and bedraggled excursionist.

Mr. Grundtvig wrote to the lord of Boyle Farm complaining of his rough reception, and demanding an apology. When none was forthcoming (did he really expect one?) he took out a summons against him to recover damages for assult. The case was heard in the King's Bench Division of the High Court, before a judge and special jury. When the whole sorry tale, with conflicting accounts from either side, was laid before the court. In his summing up Mr. Justice Lawrence told the jury it was simply a question of "which side did they believe?" In the event they decided to accept the word of the tourists. But fixed Mr. Grundtvig's damages at a mere two pounds, which could hardly have covered the expense of replacing his dog-torn garments, let alone his shattered dignity. Perhaps they concluded he had himself contributed to his own troubles (297).

Not long after this, in spite of the colossal sums of money he had expended in modernising the mansion, Mr. Robertson decided it was time to leave Boyle Farm, and he moved to a house in the Alice Holt Forest in Hampshire.

The estate was now broken up even further. In 1906 Mr. Robertson floated a company, called the Boyle Farm Estate Company Limited, with a capital of £10,000, in 10,000 shares of £1 each, and of which he was probably the sole shareholder. Its object was to lay down roads across the estate and sell land for building purposes, in what was then fast becoming a fashionable commutor area. The registered office of the company was at Station Yard, St. Mark's Hill, Surbiton (292).

Within a short time these roads appeared, and were christened with names like "Fitzgerald" and "Burtenshaw". Names which recall the story of Boyle Farm past. And were soon lined with rows of smart villas.

Mr. Robertson died at his Hampshire home on 9 November 1917 (298), and the company was voluntarily wound up by his executors just over four years later. Its work done.

Meanwhile the house itself, after standing empty for some time, was about to take on a new role. A much different role. A role which its former owners could not have conceived. And which opened its doors to an entirely new type of resident.

All books copyright © R G M Baker, all rights reserved.

Images © 2006 M J Baker and S A Baker, all rights reserved.

Web page design © 2006 M J Baker and S A Baker, all rights reserved.